I’m Dr. Keith Sakata, and this is The Signal—a newsletter that cuts through the noise to surface interesting arguments in healthcare. No fluff. Just steelmanned perspectives, deep dives, and clear thinking on medicine, policy, and innovation.

Are you new? Get free emails to your inbox every two weeks.

Today's Read: 12 minutes

The Argument

What if attention isn't just a brain circuit, but the commodity of our time? It's scarcity increases the more our society clamors for engagement. In a recent New York Times Magazine article, Paul Tough challenged the biomedical underpinnings of ADHD, arguing that we've built an ever-expanding mountain of pills atop shaky assumptions. He asks: if ADHD isn't purely biological, why is our treatment still rooted solely in biology?

So What?

This isn't just about theories. How we define ADHD shapes school policies, insurance reimbursements, workplace accommodations, and even personal identity. It governs who gets therapy versus who gets stimulants, who is viewed as "neurodivergent" versus simply distracted, and whether we continue searching for "lesions" or accept a more nuanced, systemic picture.

Let me explain.

The ADHD Controversy

In April, the New York Times ignited controversy with Paul Tough's 8,800-word exposé, "Have We Been Thinking About A.D.H.D. All Wrong?" In Tough's view, our historical treatment of the disorder rests on three assumptions:

- ADHD is a medical disorder that demands a medical solution.

- It stems from inherent deficits in children's brains.

- Stimulant medications repair those deficits.

"If we're no longer confident that ADHD has a purely biological basis, does it make sense that our go-to treatment is still rooted in biology?"

—Paul Tough, NYT

The counter-reaction was swift. Neurobiologist and science communicator Dr. Russell Barkley accused Tough of deploying "vague statements to induce worry" and resorting to "omission and selective cherry-picking" to prop up an ideological narrative. On Reddit, readers echoed the absence of grateful patient voices, epidemiologists, and contrasting data.

For skeptics of ADHD, Tough validated long-held worries: are we pathologizing normal childhood behavior in abnormal environments? Have pharmaceutical incentives blurred the line between support and overmedication? Does the DSM-5's five-of-eighteen symptom threshold invite score-tweaking ("a checkbox hack" as one critic put it) by anyone on Wall Street?

As Dr. Richard Saul quipped, "If you haven't seen the DSM-5 checklist, look it up. It will probably bother you."

By reframing ADHD as much a social construct as a neurobiological condition, Tough has forced a critical question onto every parent, educator, and clinician: Are we diagnosing real brain disorders, or enforcing cultural norms about how children (and adults) should pay attention?

This clash of paradigms is the spark that fuels today's ADHD debate.

What is ADHD and Why Are Rates Climbing?

Attention‑Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is often described as a neurodevelopmental condition marked by inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Think of it as the brain's tendency to ignore the mundane, move before thinking, and juggle too many cognitive tabs at once.

Clinically, ADHD "exists" when those tendencies cause meaningful impairment in multiple settings (school, home, or work) and typically emerge before age 12. In the U.S., about 11.4% of children ages 3-17 have received an ADHD diagnosis (13.2% of boys versus 7.0% of girls).

Yet these numbers have not plateaued. Two decades ago, 6% of U.S. kids were diagnosed; today it's one in ten.

Adult prescriptions have surged. Between 2020 and 2022, Schedule II stimulant fills rose by 30% among 20-39 year olds, some think fueled in part by pandemic-era telehealth expansions that lowered barriers to evaluation.

But not everyone agrees on why ADHD rates are climbing.

- Camp A says we’re just getting better at recognizing it—especially in groups we used to overlook, like girls and adults.

- Camp B thinks we’ve gone too far, medicalizing normal childhood behavior and handing out a trendy diagnosis that comes with real-world perks.

- Camp C points to environmental shifts—like the pandemic, online schooling, and the constant distractions of social media—as triggers that are pushing vulnerable kids over the edge.

The answer is probably a combination of the three.

First, diagnoses rates vary by race, income, and geography. These are signposts of social as much as neural determinants. Non-Hispanic Black and White children are diagnosed at about 12%. Compare that with 10% of Hispanic and only 4% of Asian kids. Children in families below the poverty line are significantly more likely to receive an ADHD or learning disability label than their higher-income peers, yet less likely to access behavioral interventions, tilting a cultural scaffold towards pills over supports.

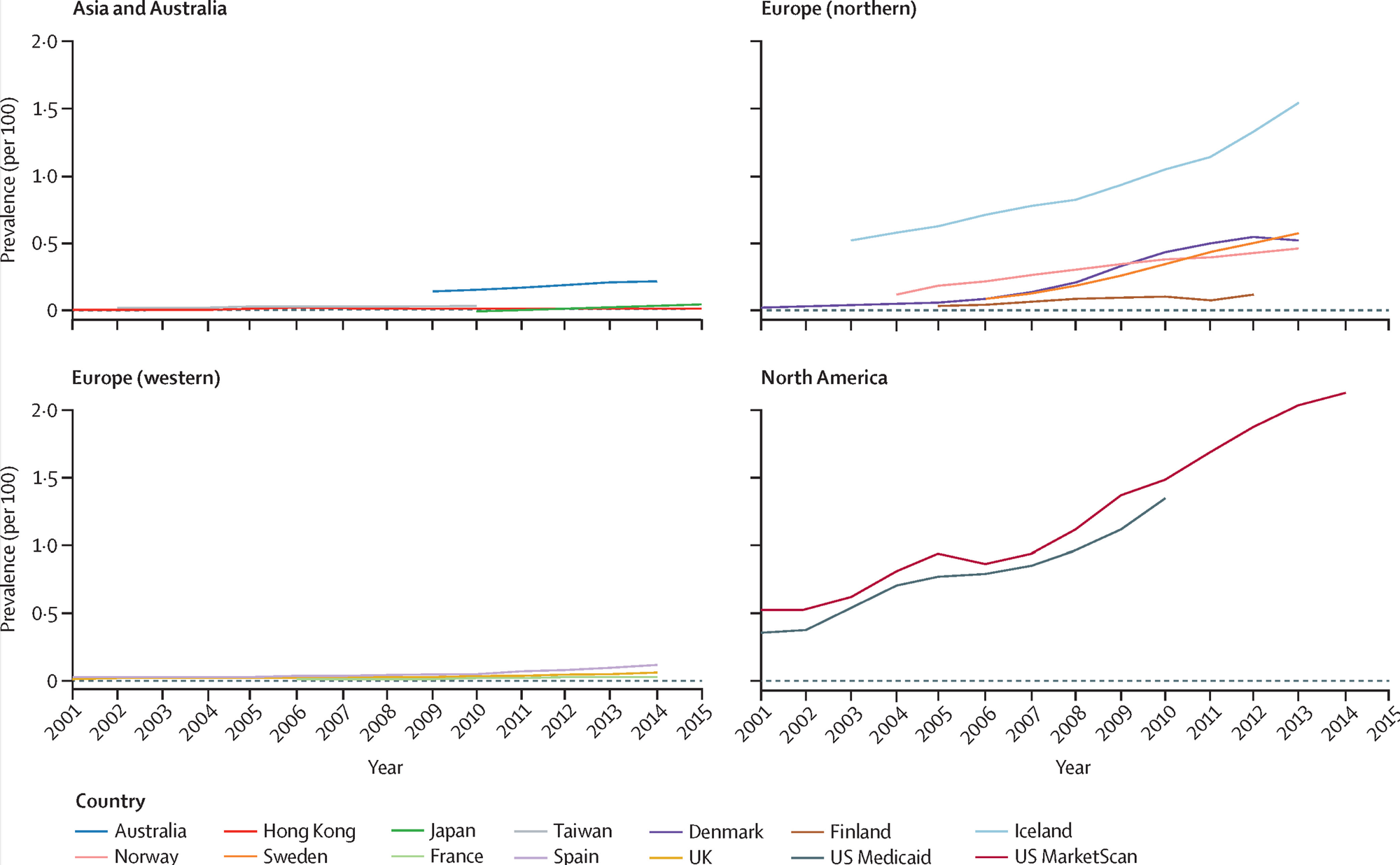

Take a look at the following global (top) and UK (bottom) trends here. There's clearly discrepancies in diagnosis and medication rates in WEIRD countries and in young adults, respectively.

Second, supply and demand are wildly asymmetric. On the supply side, ADHD medications are Schedule II controlled substances subject to DEA manufacturing quotas that often fall short of real-world demand. Since October 2022, eight major manufacturers have reported persistent Adderall shortages, fueling a secondary market that undermines equitable access. On the demand-side, up to 25% of adults think they have ADHD and self screen (with 90% false positives). Thanks to telehealth services, they're now competing directly with children and long-term patients for limited prescriptions.

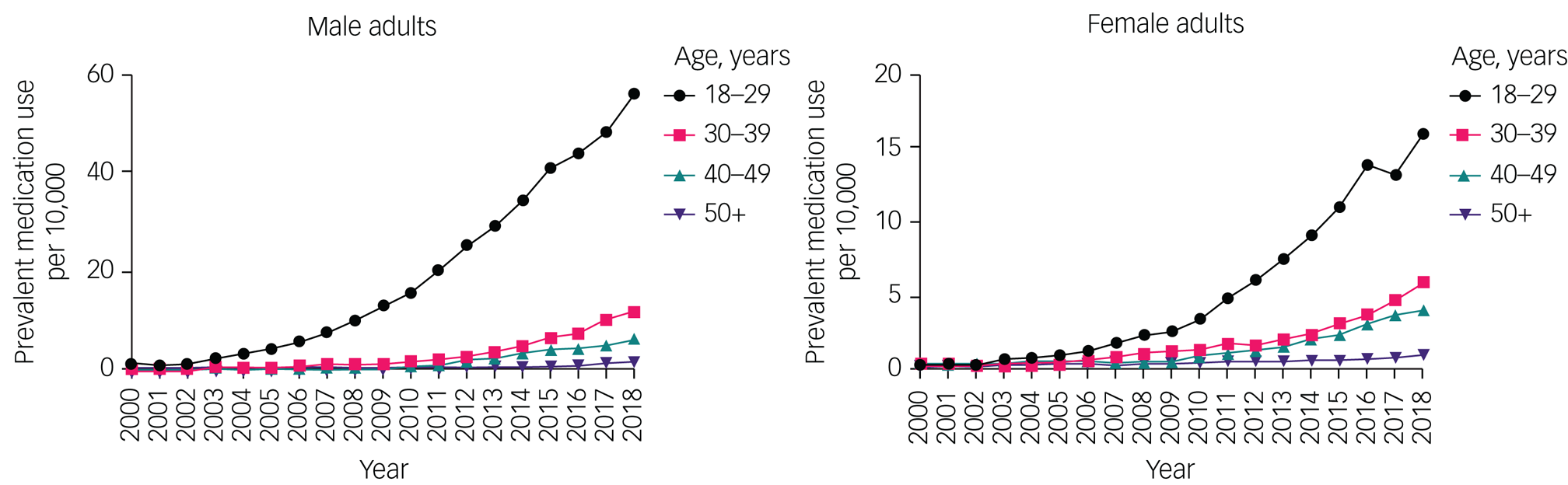

Third, the pandemic was a wellspring of public interest and clinical volume. Lockdown-driven rigidity and isolation pushed more people to ask, "Do I have ADHD?" Take a look at a few Google Trends searches I made below.

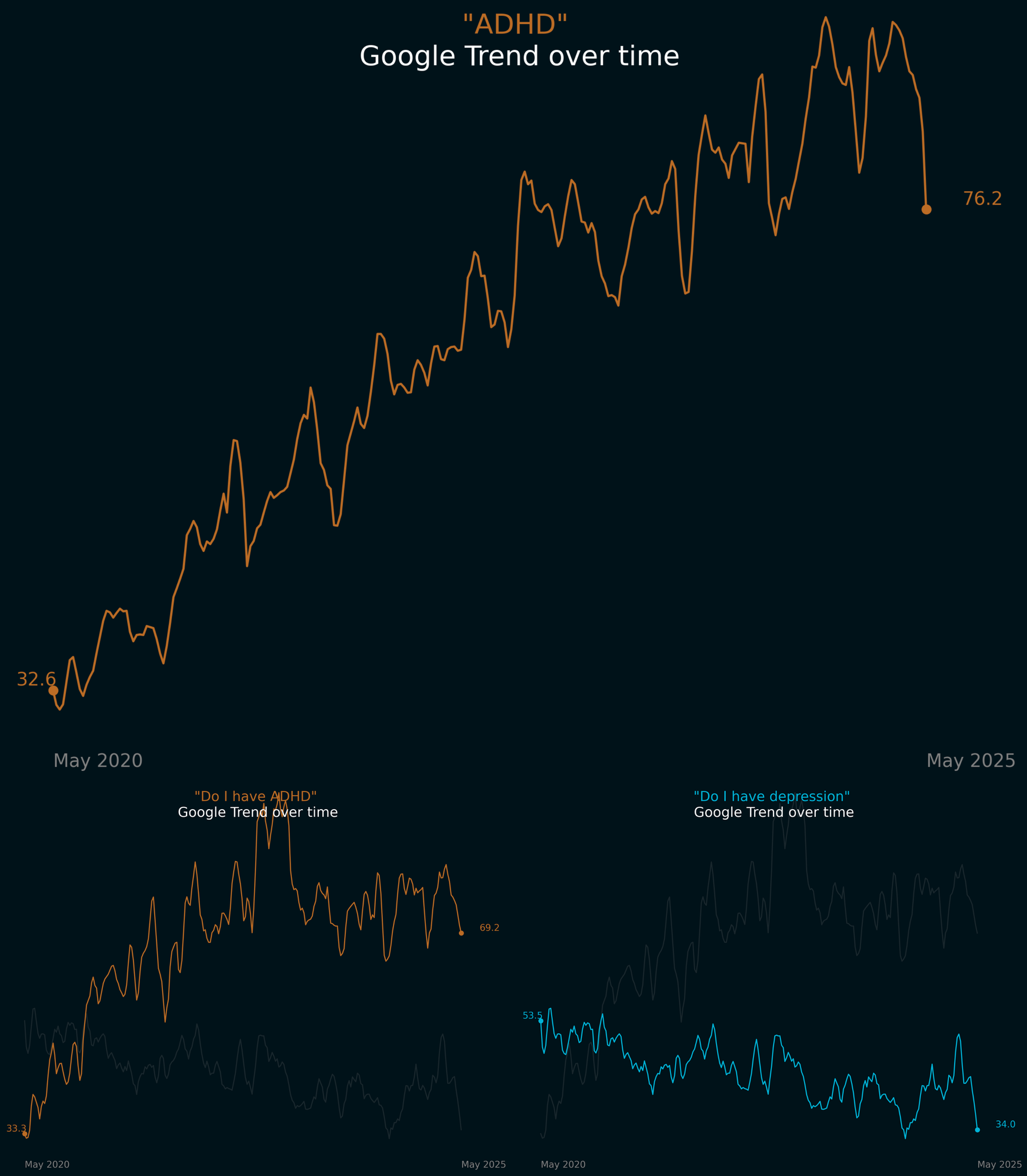

Pulling the timeline even further out, one study by Epic Research connects increasing diagnoses with revised diagnostic criteria with the DSM-5 (2013) and the pandemic (2020).

It gets even more interesting when you compare diagnostic criteria. By the criteria of the WHO 1% of German children and adolescence would qualify for ADHD, but by those of the DSM-5, the rate would be 5%.

In this landscape, ADHD becomes a window into how society allocates attention, care, and resources.

Let's finally take a look at the two sides of this issue.

The Naturalist Argument

Proponents insist ADHD is a genuine neurodevelopmental disorder despite its symptom continuity. Some compare it to hypertension (high blood pressure), where risk thresholds guide treatment even though blood pressure exists on a spectrum. Medication, they argue, is an essential tool alongside therapies and environmental supports.

“As mental health providers, we don’t diagnose people with ADHD to stigmatize or pathologize them; we do so to describe their experiences and behavior… And if we do it right, we do it well... There is much to critique in these bifurcated treatment models. Tough could have made that a central point of his article had he stepped a little farther into our world and shown a bit more empathy for the millions of folks who are in no way hapless dupes.”

—Dr. Wes Crenshaw, ADDitude

The ADHD Evidence Project underscores that continuous traits don’t invalidate biology:

“Although ADHD symptoms vary continuously across the population, this continuum does not make the diagnosis arbitrary or invalidate the disorder’s biological basis. Rather, it underscores that clinical decisions and diagnostic thresholds are established using evidence about what levels lead to meaningful impairment or increased risk of negative health outcomes.”

—Editors at the ADHD Evidence Project

Neuroimaging and genetics confirm subtle average differences in attention and impulse-control circuits. Some experts concede that no single "brain scan test reliably diagnoses an individual. But they argue that complexity is precisely why stimulants should be viewed as one among many tools, helping neurodiverse people thrive in environments that suit their unique profiles.

"The Times article closes with a recommendation that we conceive of ADHD as a mismatch between a child and his environment, and a prediction that in different environments, over a lifetime, people with ADHD may not always need stimulant meds to do well. This is certainly true — it’s an aspect of our increasingly nuanced understanding of the disorder, and the heterogeneity in the ways it presents."

—Dr. Michael P. Milham, Child Mind Institute

The Social Harm Argument

Critics warn that treating ADHD as a binary label obscures who truly needs help and inflates who “qualifies.” Rather than uncover hidden deficits, broad categorizations can become pragmatic tools: at its best to validate and identify who's most at need. And at its worst to fuel an online “ADHD identity” that distracts from the most severely impaired.

“Are psychiatrists mistaking moderately useful bins for underlying cosmic secrets?… In my practice, I’ve moved away from asking questions like ‘does this patient really have ADHD’? Those kinds of questions make me feel like I’m trying to decode their symptoms to uncover some secret variable that could be either 0 or 1. But there is no such variable. Instead, I ask ‘how much trouble does this person have with paying attention?’”

—Dr. Scott Alexander, Astral Codex Ten

By reframing ADHD categories as heuristic rules‑of‑thumb, Alexander argues that stimulants are not “magic bullets” curing a discrete disease but modulators of a complex “stew” of attention variables.

“Don’t take stimulant medications because you believe that you have a defective brain and you need the medications to fix that. That’s a terrible reason to stay on stimulants! If you were told that by a clinician, you were told an oversimplified story that you should give up. Take stimulants if they meaningfully improve your life and allow you to function better — regardless of whether ADHD is a 'medical disorder.'"

—Dr. Awais Aftab, Psychiatry at the Margins

On Substack, Freddie deBoer critiques the ADHD activist movement as a social contagion:

"We are told, with great aggression, that there’s nothing wrong with ADHD or autism, that having those conditions is not in any sense a negative... however, we are simultaneously told that people with autism and ADHD have an absolute right to demand formal legal accommodation. An inevitable and ugly part of the popularization and casualization of these disorders is that the people who are actually badly afflicted by them become marginal in their spaces, the gentrification of disability."

—Freddie deBoer, Substack

My Take: ADHD at the Intersection of Neurology and Culture

What if ADHD isn't a binary condition but an emergent property of complex systems? A multidimensional space where neurobiology meets societal expectations.

The most illuminating question isn't whether ADHD is "real," but rather: at what point does an ADHD diagnosis reveal more about our culture than about individual neurochemistry?

The False Binary of Nature vs. Nurture

When we debate whether ADHD is "biological" or "societal," we're setting up a false dichotomy that serves neither patients nor science. Consider three competing models:

- The Pure Biological Model: ADHD represents a discrete neurobiological condition characterized by dopamine dysregulation and prefrontal cortex dysfunction.

- The Pure Social Construction Model: ADHD is merely the medicalization of normal human variation, invented to sell pills and enforce conformity in classrooms and workplaces.

- The Dynamic Spectrum Model: ADHD exists along multiple continuums where neurobiological vulnerabilities interact with environmental demands and cultural expectations.

I believe the evidence overwhelmingly supports the third model. A common slogan in psychiatry is that "ADHD is simultaneously both under-prescribed and over-prescribed." This seeming contradiction dissolves when we recognize that ADHD isn't a single thing but a constellation of traits that manifest differently across individuals and contexts.

There are those with severe dysfunction that aren't getting help due to different cultural values and/or stigma. At the same time, there is definitely something interesting happening with ADHD influencers on Tiktok.

Why "Show Me the Lesion" Misses the Point

Is "non-biological" just a placeholder for "poorly understood?"

Probably.

Our understanding of disease has always been limited by our technological capacity to observe it. Consider the historical trajectory:

- Epilepsy shifted from "demonic possession" to neurophysiology with the invention of EEG.

- Endometriosis went from "normal period pain" to gynecologic diagnosis under a microscope.

- Rheumatoid arthritis was once hypothesized to be a lifestyle consequence of the industrial revolution before modern immunology revealed its mechanisms.

The diseases didn't change—our ability to observe them did.

Today's "non-biological" problem is often tomorrow's brain network-level insight. If we hold ADHD hostage to the absence of a visible lesion, we'll always be one technological leap behind—and people will suffer without appropriate treatment.

Perhaps the most provocative question is whether our society's values have outpaced human capacity. Attention has become our scarcest resource—scarcer even than time. In an economy built on capturing and monetizing attention, those at the left side of a Gaussian distribution for attention are in for trouble.

You might feel compelled to ask:

Why don't we give Adderall to everyone?

To be clear, I think this is a terrible idea. But lets put the litany of side effects and risks of harm aside for a second.

This question cuts to the heart of our discomfort with cognitive enhancement. Stimulants improve concentration for virtually everyone—not just those with ADHD. If we acknowledge this truth, we must confront whether our diagnostic thresholds accurately map onto genuine suffering or a competitive disadvantage in a society anxiously fixated on status.

The story is different for those with severe ADHD.

The "honeymoon phase" of stimulant treatment reveals a telling paradox: long-term users often describe their medication not as a miracle but as a "necessary evil." The initial euphoria and hyper-focus inevitably wanes, leaving behind a more modest improvement in sustained attention.

Meanwhile, behavioral interventions (meditation, cognitive-behavioral therapy, environmental modifications) show meaningful, if modest, improvements. These approaches raise baseline functioning in ADHD populations, suggesting they're improving societal-cognitive fit rather than repairing a deficit.

Here's where I disagree with the New York Times.

I've spent years tutoring kids who fidget through every classroom lesson, blurting out answers, and drifting off mid-sentence. And when I diagnose ADHD as a clinician, I'm naming more than a checklist. I'm articulating the real distress patients and their families feel.

This distress and dysfunction leads to consequences like more substance use, lower socioeconomic advancement, and premature death (up to 8 years for women with ADHD).

Anyone who wants to replace medications with a Platonic ideal of "therapy + lifestyle + societal reorganization" should be able to name a specific set of concrete interventions for which they can demonstrate high quality evidence for it's efficacy.

“Do not remove a fence until you know why it was put up in the first place.”

The Chesterton's Fence

It's a reminder to understand something before you change it, to respect the past, even if you want to change the future.

Beyond the Dichotomy

ADHD sits at the crossroads of neurobiology and culture, where shifting norms, digital environments, and administrative incentives converge. Treating it as either purely a brain disease or purely post-internet culture blinds us to the real challenge: adapting our values to honor human variability.

I don't think that diseases can be 100% free of subjectivity and social values. (yes even heart attacks)

The word disease or disorder implies a dysfunction. And dysfunction is linked to values that transforms over times and cultures. What is or is not a failure is a judgement, not a natural expression of organic function. And as is the case for ADHD, the less we know about disease mechanisms, the lower the expected agreement concerning values in dysfunction.

Mental functions are directly linked to social role function in a way that other more physical processes are not. This brings them closer to sociocultural values. There is an implication of the existence of a social scaffold that someone must fit.

Therefore I think the "true disorder" = biology perspective is a fallacy.

Disorders are useful constructs in that they allow us to predict interventions to use and how to think about prognosis.

I disagree with Tough in his claim that biological treatments are only reserved for "biological" conditions. Because this is a fluid reality: new evidence and methods bring new ways of classifying and defining disease. And a physician's role is to prevent and relieve suffering to prevent premature, avoidable death.

At the same time, I do agree with Tough that the truth lies not in choosing between competing models but in integrating them. Most people diagnosed with ADHD have varying blends of neurobiological vulnerability and environmental reinforcement. For some it may be 70% biology, 30% environment; for others the inverse.

Perhaps the most important insight comes from recognizing that our categorization systems are tools, not truths.

The DSM-5's eighteen-symptom checklist is a heuristic. It's a pragmatic shorthand for a complex reality. If we mistake these heuristics for immutable truths, we run the real risk of turning human variability into a lifetime subscription to a diagnostic label and pharmaceutical intervention.

Our challenge, then, is not to resolve whether ADHD is "real" but to develop more sophisticated models that capture its multidimensional nature—and interventions that address both individual neurochemistry and the attention economy that increasingly demands superhuman focus from a normal distribution of human brains.

Don’t see it the same way? That’s fair—this is just one perspective. Share your thoughts by replying to this email or commenting, and we might feature your response.

By The Numbers

- 58% — The increase in U.S. stimulant prescriptions for ADHD between 2012 and 2022, rising from 61 million to 96 million annually.

- 15.5 million — Estimated U.S. adults with ADHD in 2023, up from 4.5% prevalence in 2003 to 6% today.

- 30.1% — Percentage of children with diagnosed ADHD receiving no ADHD-specific treatment.

- $143–$266 billion — Estimated annual U.S. economic cost of ADHD, the majority borne by adults.

- 61% — Share of young adults (18–24) who stop taking ADHD medication within a year of starting.

- 3x — Relative risk of nicotine dependence in people with ADHD compared to those without.

- 21% — Proportion of 14-year-old boys in the U.S. diagnosed with ADHD—double the overall child rate.

- 9% — Share of children once diagnosed with ADHD who show no symptoms by adulthood.

- 80% — Proportion of ADHD stimulant abusers that are aged 12-25 years old.

- 0.19% — Rate of psychotic symptoms in children treated with ADHD medication in clinical trials—well below the general population baseline of 10%.